Only a Paper Moon

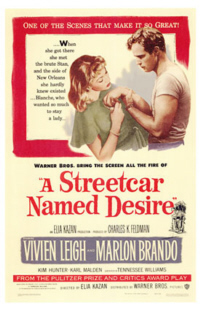

Marlon Brando and Vivien Leigh give outstanding onscreen performances in Tennessee William's play brought to Hollywood by Elia Kazan. Strongly supported by Kim Hunter and Karl Malden, Leigh is unforgettable as the decaying Southern belle in this profoundly human drama captured on film. TVO's Saturday Night at the Movies brings this film classic to the small screen.

Marlon Brando and Vivien Leigh give outstanding onscreen performances in Tennessee William's play brought to Hollywood by Elia Kazan. Strongly supported by Kim Hunter and Karl Malden, Leigh is unforgettable as the decaying Southern belle in this profoundly human drama captured on film. TVO's Saturday Night at the Movies brings this film classic to the small screen.

A Streetcar Named Desire Video Trailer (IMDb)

It’s a steamy summer night. I hear a police siren screaming through the open window along with the heavy, humid evening air. In the residential area where I sit as I write this entry, chances are about equal that the emergency vehicle may be on its way to investigate the latest corner store hold-up or that it may arrive at the scene of some form of domestic violence.

It would be easier if we could all just pretend that such heinous things almost never happen. But they do happen. And it can happen right in our own backyard: A twelve year old girl participates with her much older boyfriend in the cold-blooded murder of three of her immediate family members. A man in a quiet suburb of our city blows up his wife and children in a fireball of revenge, murder and suicide. A friend of mine lives with daily uncertainty as to whether her estranged husband’s anger and frustration will degenerate from verbal to physical violence.

It is not a pretty picture. There goes the siren again. I could close the window to keep the noise of the siren out – but that wouldn’t really make the problem go away. More than likely, in this large urban area, there will be some incident of domestic violence that unfolds over the next few hours that the police will have to investigate. Most of us, as bystanders, look on with eyes wide shut to the horror and the pain of the domestic turmoil that lives next door to us.

Tennessee William’s A Streetcar Named Desire has been committed to cinematographic immortality in the magnificent 1951 adaptation of his stage play directed by Elia Kazan. The Interviews (July 7/07) on TVO reference William’s full participation in the Hollywood version of this stage masterpiece. Much could be said of the excellent dialogue provided by Williams that serves as the basis for creating the unforgettable characters of the screenplay.

Kazan had previously directed the Broadway version of the stage play in New York . Although many of the award winning elements such as the taut jazz music score, the subtle use of lighting, the black and white cinematography, and the evocative set design contribute enormously to the success of the production, to me it is the casting that makes the movie. (Oh! Did I mention costume design? Stanley ’s T-shirts, of the ripped or unripped variety, are just - well - Stanley ’s T-shirts. But Blanche’s fabulous flouncy

Kazan had previously directed the Broadway version of the stage play in New York . Although many of the award winning elements such as the taut jazz music score, the subtle use of lighting, the black and white cinematography, and the evocative set design contribute enormously to the success of the production, to me it is the casting that makes the movie. (Oh! Did I mention costume design? Stanley ’s T-shirts, of the ripped or unripped variety, are just - well - Stanley ’s T-shirts. But Blanche’s fabulous flouncy  summer dresses together with the other finery of the fading southern belle – now there’s some material for the costume designer to work with!)

summer dresses together with the other finery of the fading southern belle – now there’s some material for the costume designer to work with!)

When the stage play emigrated from New York to Hollywood , Williams the writer and Kazan the director as well as the majority of the original cast went along for the trip. It was a move that was considered unusual. A key decision was made, however, concerning the part of “Blanche”. (Ugh! Yuck! I can hardly bring myself to say the name the way they do in the film. The southern accent softens it up some in English, but still, the sound is so preposterously nasally and harsh, so totally unrefined and unromantic compared to the way the name is said in the original language!)

The decision was made to give Jessica Tandy’s role to the British “Blanche” – Vivien Leigh. Leigh had developed her version of the role in London under the stage direction of her husband, Laurence Olivier. Apparently the decision was made in Hollywood on the basis of the anticipation of greater box office success with Leigh’s name headlining. Whatever the reasons for the decision, it turned out to be a good one. Leigh is riveting as the coquettish and emotionally fragile Blanche.

Sadly, the line drawn between the onscreen invention and real life may have been more blurry than one cares to discover. If the details of stories concerning Leigh’s troubled marriage to the longsuffering Laurence Olivier are more than tabloid gossip, and if the even more troubling observations of nymphomaniac behaviour are factual, one certainly has something to think about.

Perhaps it is the case that Vivien Leigh played the part of Blanche like no other. Perhaps our delight in the convincing portrayal of the character of Blanche Dubois preserved forever on film does not take into account the personal pain that went into the performance. Leigh’s own struggle with mental illness in the form of bipolar depression did not end when the curtain came down. It had devastating real life consequences, just as it does for people in all professions and walks of life.

The character Blanche finds herself in the unfortunate position of not only being the poor relative come to call, but of getting between her sister, Stella, and her husband, Stanley. Stella and Stanley have one of those crazy sorts of relationships where they are fighting like cats and dogs one minute and all over each other the next minute. (It seems to be going around. The couple in the apartment upstairs, Steve and Eunice, spend their time doing pretty much the same thing.)

Stanley has a reputation for being a bit of a hell-raiser. It doesn’t take much; a dig from Blanche about how Stanley is “too common” for her sister, the music on the radio played a little too loudly interrupting the poker game. Stanley’s temper flares. He is a violent man. The alcohol doesn’t help either. Of course, as Stella is quick to add, after such incidents, Stanley is “really very ashamed of himself” and is “as good as a lamb”. Stella is all too willing to forgive and forget. In fact, Stella freely admits that Stanley ’s unpredictable and dangerous streak was something she was “sort of thrilled by” as per the “broken lightbulbs on the honeymoon” rampage.

Stanley has a reputation for being a bit of a hell-raiser. It doesn’t take much; a dig from Blanche about how Stanley is “too common” for her sister, the music on the radio played a little too loudly interrupting the poker game. Stanley’s temper flares. He is a violent man. The alcohol doesn’t help either. Of course, as Stella is quick to add, after such incidents, Stanley is “really very ashamed of himself” and is “as good as a lamb”. Stella is all too willing to forgive and forget. In fact, Stella freely admits that Stanley ’s unpredictable and dangerous streak was something she was “sort of thrilled by” as per the “broken lightbulbs on the honeymoon” rampage.

It seems that Stella doesn’t always understand what sets her husband off. She walks right into the ambush time and time again. Perhaps in this way Blanche really does understand Stanley better. It seems that Stella is too taken up with living in the moment, taking the good with the bad, to really delve into what’s going on with Stanley . Stanley might think it perfectly acceptable to observe that he has pulled Stella down off of “one of those high columns”. But as far as Stanley is concerned, he needs his wife to keep him up there in her regard on the top of one of those white marble pedestals; “every man a king in his own home”. Sister Blanche is a threat. He’ll do just about anything to get rid of her.

It seems that Stella doesn’t always understand what sets her husband off. She walks right into the ambush time and time again. Perhaps in this way Blanche really does understand Stanley better. It seems that Stella is too taken up with living in the moment, taking the good with the bad, to really delve into what’s going on with Stanley . Stanley might think it perfectly acceptable to observe that he has pulled Stella down off of “one of those high columns”. But as far as Stanley is concerned, he needs his wife to keep him up there in her regard on the top of one of those white marble pedestals; “every man a king in his own home”. Sister Blanche is a threat. He’ll do just about anything to get rid of her.

Stanley is a pretty direct, "no nonsense" type of guy. Blanche, on the other hand, could not bring herself to be “straight” even if her life depended on it: “Straight? What’s straight? A line can be straight, but the human heart . . .?” Indeed, Blanche does have quite the problem with what she calls her little “fibs”. It’s not so much that she intends to deceive people – “I don’t want realism! I want magic! I try to give people that. I do misrepresent things. I don’t tell the truth. I tell what ought to be the truth. If that’s a sin, may I be punished for it!”

It seems that Blanche is so caught up in her imagined reality of la noblesse déchue that she must stay out of the harsh light of day in order to preserve some of her most cherished ideals. She lives by the kinder, gentler light of a paper Chinese lantern placed carefully over the naked electric lightbulb.

It seems that Blanche is so caught up in her imagined reality of la noblesse déchue that she must stay out of the harsh light of day in order to preserve some of her most cherished ideals. She lives by the kinder, gentler light of a paper Chinese lantern placed carefully over the naked electric lightbulb.

But even as her world is coming unravelled, Blanche is very strong on at least this one point: “Some things are not forgivable. Deliberate cruelty is not forgivable. It’s one thing I’ve never been guilty of.” Stanley may be deliberately cruel to her, the townspeople of her hometown, the accusatory Mr. Shaw, and even life itself may be cruel to her. But of this one thing, Blanche is very certain; she herself has never stooped so low as to engage in deliberate cruelty.

Or has she?

You never know with Blanche . She tells quite a different tale when she finally explains to her suitor, Mitch, what had actually happened to her first husband many years before. In a moment of vulnerability with Mitch, Blanche reports saying that she told her emotionally fragile young husband, “You are weak. I’ve lost respect for you. I despise you!” The young man proceeded to go off and shoot himself in the head.

I don’t know. Those sound like pretty cruel words to me.

The conscious mind including the human conscience is a remarkable thing. Who can explain exactly how it works? I remember once hearing a doctor who worked at a mental health institution saying, “You know, if only people could know for sure that they were forgiven, half the folks here could go home.” I have no idea, all these years later, who that professional was, how credible his statement was or even how near to the mark his estimates are. I just know that it’s a statement about mental health that has to apply to some of the people some of the time.

The conscious mind including the human conscience is a remarkable thing. Who can explain exactly how it works? I remember once hearing a doctor who worked at a mental health institution saying, “You know, if only people could know for sure that they were forgiven, half the folks here could go home.” I have no idea, all these years later, who that professional was, how credible his statement was or even how near to the mark his estimates are. I just know that it’s a statement about mental health that has to apply to some of the people some of the time.

I reckon that Blanche may very well fit into that category. Blanche finds deliberate cruelty to be unforgivable in others and in herself. She is never quite able to get over the event. It is easier to rewrite history, to invent an alternate personal scenario, to keep up a façade with the whole world than to face the ugliness in her own soul. The “shimmering” as Blanche calls it, has taken up a great deal of her energy in order to maintain appearances.

When Mitch later confronts her with the fiction of her recent goings on as the mistress of the deteriorating Belle Rive estate, Blanche maintains rather desperately, “But I never lied in my heart!” For her, the latest invention of the unexpected Caribbean cruise that she weaves together for Stanley is a truer version of reality. Almost lost in her flight of fancy, in her own mind, Blanche is truly a cultivated woman possessing an unparalleled “beauty of the mind, a richness of spirit and a tenderness of heart” instead of a broken-down, penniless alcoholic with sordid sexual habits.

When Mitch later confronts her with the fiction of her recent goings on as the mistress of the deteriorating Belle Rive estate, Blanche maintains rather desperately, “But I never lied in my heart!” For her, the latest invention of the unexpected Caribbean cruise that she weaves together for Stanley is a truer version of reality. Almost lost in her flight of fancy, in her own mind, Blanche is truly a cultivated woman possessing an unparalleled “beauty of the mind, a richness of spirit and a tenderness of heart” instead of a broken-down, penniless alcoholic with sordid sexual habits.

The world soon closes in on Blanche as she finds herself being taken away to the asylum. After a few moments of hysterics, Blanche regroups and manages to put forward a heart wrenching air of dignity as she walks into her unknown future on the arm of the attendant: “Whoever you  are, I’ve always depended on the kindness of strangers.”

are, I’ve always depended on the kindness of strangers.”

My, what a wild ride we’ve had on the Streetcar Named Desire. Canadian film maker Harry Rasky, quoted in the Interviews (July7/07), sums it up well: “He (Tennessee Williams) gave me such a greater patience and understanding of people who are fragile. He made me understand that you have to love people for what is wrong with them rather than for what is “great” about them. Because what is “great” about them may be what made them fragile.”

In this insane, mixed up and sometimes cruel world Williams does a beautiful job of showing us that we could all use a little more understanding in the midst of the fragility of our human condition.

Suggested Explorations in Cyberspace:

- The song “It’s Only a Paper Moon” – one of Blanche’s favourites . I’m particularly partial to the Ukelele Ike (Otherwise known as Jiminy Cricket) version available for download here.

- “What?! You’re going bowling now?!” Help for couples stuck on the crazy cyle: his’n’her needs – respect and tenderness. Video

- Living through an abusive relationship- One woman escapes the shark pool of a controlling relationship; another finds hope and love

- Fib Fixer: learning to trust (and be trustworthy) so you can throw away the paper lanterns

- Handling turbulent times in domestic relationships productively